The Senate’s passage of the Marketplace Fairness Act last week, on a 69-27 vote, marks a watershed in the 20-year fight to extend the requirement to collect state and local sales taxes, long imposed on brick-and-mortar retailers, to their large online and mail-order competitors.

The bill, which allows states to compel remote retailers to collect sales taxes if they have more than $1 million in internet and mail order sales, faces a tougher road in the House, where some conservatives have vowed to block it. But momentum from the lopsided Senate vote, the bill’s two dozen Republican co-sponsors, and sustained pressure from Main Street retailers may well win the day. President Obama supports the measure.

Passing this bill is imperative for anyone concerned about fairness. There’s no good reason government should be giving consumers a 4 to 10 percent incentive to choose online retailers over local stores. Nor should someone who, say, buys wedding invitations from an online vendor or a television set from Amazon get a pass on supporting her state’s schools and services, while her neighbor who prefers local shops gets stuck with the tab. (Technically, shoppers owe sales tax even when an online seller doesn’t collect it, but fewer than 1 percent of people actually send the money to their state.)

Nevertheless, a looming question is how much difference correcting this disparity will make at this late date. Had Congress acted a decade ago (or way back in 1992 when the U.S. Supreme Court explicitly invited it to look at the issue), many independent Main Street retailers would still be in business and our online shopping landscape would almost certainly be more diverse and dynamic than it is. Today, Amazon — which, in addition to its namesake site, owns dozens of internet brands, including Zappos and Diapers.com — accounts for a staggering one-third of all the items we buy online. The company posted $61 billion in sales last year, almost double its 2010 revenue.

Amazon’s success is a product of its own ingenuity together with a huge helping hand from government. Although the retailer has always insisted that getting a free ride on sales tax is not integral to its strategy, its actions suggest otherwise. In an unguarded interview with Fast Company in 1996, a year after Amazon launched, founder Jeff Bezos said that avoiding sales taxes drove the company’s decision to locate in Seattle. California had the technical talent that Amazon needed, Bezos explained, but locating in such a populous state would mean forfeiting its ability to peddle goods sales-tax free to a large swath of the U.S. population. (Under current law, retailers must collect sales tax in states where they have a physical location or other tangible “nexus.”)

Holding on to this competitive edge was a top priority for Amazon for the next 15 years. According to the Wall Street Journal, the company maintained a map showing states where employees were barred from traveling unless they were first grilled by a lawyer and outfitted with special business cards indicating they worked for a subsidiary, rather than Amazon.com, lest their activities trigger nexus for sales tax purposes. Clearly, Amazon believed collecting sales taxes would eliminate its competitive edge and doom its growth.

As it expanded, Amazon played states against one another to win deals allowing it to build warehouses and still not collect sales taxes. By 2010, it was operating in 17 states but collecting sales taxes in only 4. Amazon even went so far as to conceal its presence in some states. Texas officials, for example, were unaware that Amazon operated a giant warehouse in the state until the Dallas Morning News published an expose on the retailer’s tax-dodging. When the state sued for $269 million in back sales taxes, Amazon threatened to shut down the facility and fire hundreds of people in retaliation. The state eventually canceled the tax bill after Amazon offered to build additional facilities in Texas.

With its warehouses proliferating and more states adopting laws that effectively block its tax evasion — Amazon is now collecting sales taxes in nine states containing one-third of the U.S. population — the company gradually began to concede the fight. A turning point came in 2011, when Amazon dropped an expensive referendum fight in California and agreed to collect sales taxes in that state beginning in September 2012. Having acquiesced to the inevitability of sales taxes, Amazon is now planning to build warehouses in every major city to provide same-day delivery and is using the promise of jobs to secure a host of new tax breaks and subsidies. The retailer has even voiced support for the Marketplace Fairness Act, presumably so its internet rivals would also have to collect sales taxes and Amazon wouldn’t find itself operating at the same disadvantage Main Street retailers have suffered for years. Indeed, the company is lobbying to get rid of the $1 million exemption and apply the bill to even the smallest online sellers.

While it’s impossible to see Amazon as anything other than a horse that’s already out the barn door, there’s still good reason to believe that the Marketplace Fairness Act will slow its consolidation of retailing and provide some benefit to small independent businesses.

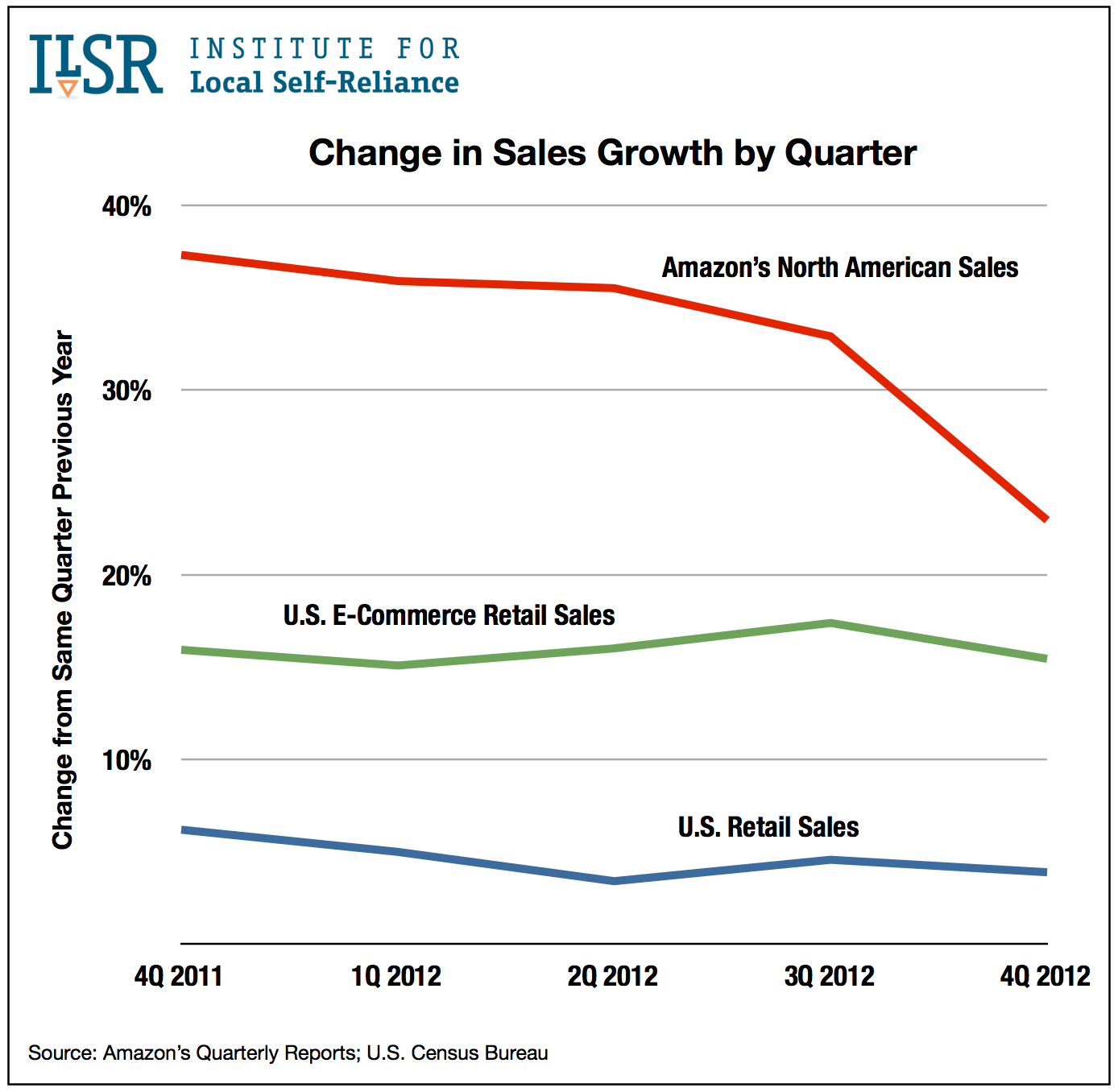

Amazon’s own recent sales figures suggest as much. The company’s North American sales growth slowed markedly in the 4th quarter last year, just as it began collecting sales taxes in California, Texas, and Pennsylvania (see this graph). The deceleration of Amazon’s growth was much steeper than the relatively modest overall slowdown in U.S. retail sales growth and it occurred even as Amazon’s cloud services business (which is not subject to sales taxes) was expanding rapidly and thus masking even weaker retail sales growth.

Amazon’s own recent sales figures suggest as much. The company’s North American sales growth slowed markedly in the 4th quarter last year, just as it began collecting sales taxes in California, Texas, and Pennsylvania (see this graph). The deceleration of Amazon’s growth was much steeper than the relatively modest overall slowdown in U.S. retail sales growth and it occurred even as Amazon’s cloud services business (which is not subject to sales taxes) was expanding rapidly and thus masking even weaker retail sales growth.

Meanwhile, Best Buy, which charges sales taxes everywhere, reported that its online sales have been growing faster in states where Amazon now collects sales taxes. Anecdotal reports from independent bookstores and others suggest that local retailers in these states are feeling a benefit too.

Nor is Amazon the only large retailer that would have to start playing by the same rules as local stores. Of the 184 web-only companies on Internet Retailer’s list of the Top 500 online retailers, 155 currently collect sales taxes in fewer than four states. This includes companies like Overstock and Newegg, which have annual revenue north of $1 billion.

The Marketplace Fairness Act will close part of the price gap between independent retailers and these large online sellers, giving local stores a better chance of using their personalized service, community ties, and in-store experience to overcome the rest. It will also improve their ability to create multichannel relationships with their customers (i.e., sell to them both in-store and online). Because their customer base is mostly local, independent retailers have always had to charge sales taxes on most of their internet orders, making it that much harder to compete for a piece of the shopping their customers prefer doing online. Passage of this bill will make that opportunity easier to grasp.

Local retailers deserve that at the very least. They’ve been providing jobs, filling storefronts, paying taxes, outfitting Little League teams, and otherwise contributing to the life of our communities, even as Congress, year after year, has stood by a tax policy that puts them at a significant competitive disadvantage. While the right moment to enact the Marketplace Fairness Act has long since passed, we now have another moment before us and it still very much matters.

This piece originally appeared on Alternet.