This article was originally published on Huffington Post as part of a partnership with their Move Your Money campaign.

Bigger banks were suppose to lower costs for consumers. That was the promise made repeatedly in 1994 and again in 1999, when Congress dismantled laws that had long restricted the size and scope of banks, ushering in a wave of mergers that left the industry dominated by a few financial giants.

Testifying in support of the so-called Financial Services Modernization Act in 1999, Michael Patterson of J.P. Morgan used the word “consumer” no less than twenty-one times in his remarks. He told Congress that freeing up big banks to get even bigger would provide consumers with “greater convenience, more innovation, and lower costs.”

Many regulators and lawmakers echoed his assertions. Robert Rubin, then Secretary of the Treasury and later a director at Citigroup, said that the “reforms” would “lead to better service and lower costs.” Congress passed the bill by wide margins and President Bill Clinton enthusiastically signed it into law, promising that the changes would “save consumers billions of dollars a year through enhanced competition.”

Just seven years later, the fees consumers were paying on their checking and savings accounts had skyrocketed, rising from $21 billion in 1999 to $36 billion in 2006. (And these amounts do not include credit card and ATM fees, which also shot up.)

That bigger banks would mean higher prices was plainly evident in 1999 to anyone who bothered to consult the data. For the previous five years, the Federal Reserve had issued yearly reports to Congress that showed that bigger banks charged significantly higher fees on checking and savings accounts.

That bigger banks would mean higher prices was plainly evident in 1999 to anyone who bothered to consult the data. For the previous five years, the Federal Reserve had issued yearly reports to Congress that showed that bigger banks charged significantly higher fees on checking and savings accounts.

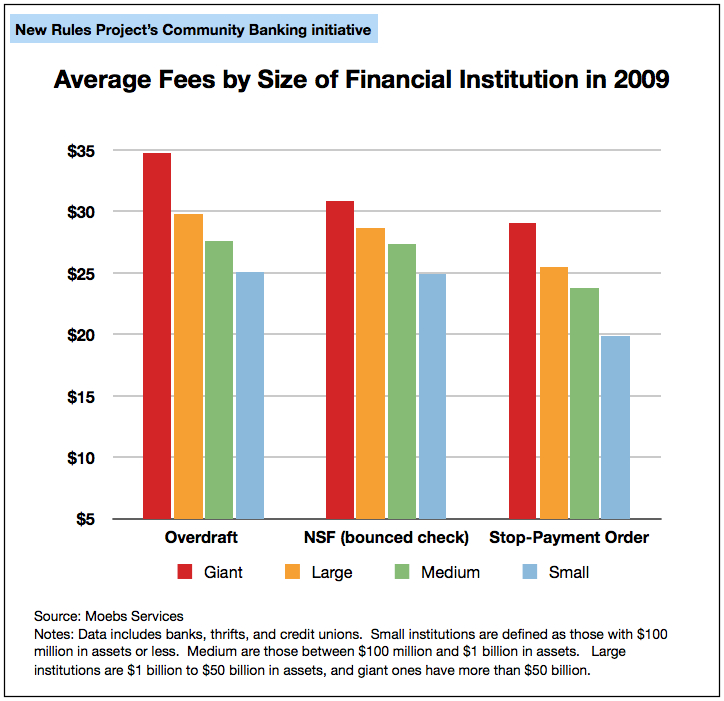

The Fed’s 1999 report, published five months before the Financial Services Modernization Act passed, found that overdraft fees were 41 percent higher at big banks compared to small. Big banks charged more for almost every fee imaginable, including 43 percent more for bounced checks, 57 percent more for stop-payment orders, and 18 percent more for ATM withdrawals.

But rather than allow the evidence in favor of smaller banks to guide policy, Congress decided to get rid of the evidence. At the urging of then Fed chairman Alan Greenspan, Congress ordered the Federal Reserve to stop publishing its annual report on bank fees. “The Fed fought to get rid of it,” said Ed Mierzwinski, consumer program director at the US Public Interest Research Group. “They said transparency was not a good use of their resources.”

For most of the last decade, information on the average cost difference between big banks and small local financial institutions has not been publicly available. But, as it turns out, the firm that the Fed once employed to gather this data, Moebs Services, has continued to survey fees at more than 2,000 financial institutions. Moebs agreed to share its 2009 data with the New Rules Project. As our chart shows (click for a larger version), the biggest banks still impose much higher costs on their customers than small financial institutions do.

Not only are fees lower, but several studies have found that smaller banks and credit unions pay higher interest on savings accounts. In a study published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, researchers Kwangwoo Park and George Pennacchi examined data from 1998 to 2004 and found that rates on one-year CDs were an average of 14 percent higher at small banks (under $1 billion in assets) than at large ones (assets of $10 billion or more) and rates on interest-bearing savings accounts were 49 percent higher.

Why are small banks and credit unions a better deal? One reason is that they really want your deposits. Unlike big banks, which have access to wholesale funding, community banks rely much more on customer deposits to finance their lending and investments.

A second reason is that many small banks are more efficient than their big competitors. That may seem surprising at first. In many industries, more volume lowers costs, but in banking there’s an upper limit – a point at which a bank’s bloated bureaucracy makes the cost of doing everything more expensive, not less. Exactly where that threshold lies is a matter of debate, but some analysts suggest that the sweet-spot for efficiency starts as low as $500 million in assets and ends once a bank hits $4 or $5 billion. To put that in perspective, Bank of America and J.P. Morgan Chase are about 300 times that size.

But perhaps a more instructive question to ask is not why are small banks a better deal, but how do big banks get away with charging so much more? After all, people have a choice about where to bank and free markets are suppose to drive down prices.

Christopher Peterson, an expert on consumer finance at the University of Utah School of Law, says there are two main theories. Those who believe the market is working contend that “bigger banks have more comprehensive branch locations, so people will pay a premium for convenience.”

Another explanation is that banks are adept at obscuring their prices and make it hard to comparison shop. “I think our impulse in this country is to overestimate the ability of people to shop down fees that are not transparent,” said Peterson.

Indeed, the Government Accounting Office recently sent secret shoppers into 185 bank branches. They were unable to obtain detailed information on account terms at one-third of those branches and unable to obtain a comprehensive schedule of fees at one-fifth, despite the fact that such disclosures are required by federal law – a law that apparently is not enforced. More than half of the banks did not provide this information on their web sites, either. (Here’s the GAO’s report.)

Mierzwinski says big banks have the advantage of having recognizable names and branches everywhere. Many people simply go to the nearest big bank branch and don’t shop around. “They particularly don’t compare the bank’s penalty fees, which are so hard to find,” he said. “Everyone advertises free checking, but ‘free’ only defines monthly maintenance fees.”

If you bank at a big bank, all of this should prompt you to give some serious thought to ditching it. Even if you are good at avoiding penalty fees, why do business with a bank that charges exorbitant prices and attempts at every turn to hit its depositors with sneaky fees? Shop around instead for a institution that treats its customers fairly. Consumer advocacy groups say the best place to start is with local credit unions and community banks. The smallest have the lowest costs on average. But keep in mind that averages are just that; institutions vary and each should be evaluated individually according to how well it meets your needs and how responsive it is to your community.